Cavitation can upset basic principles.

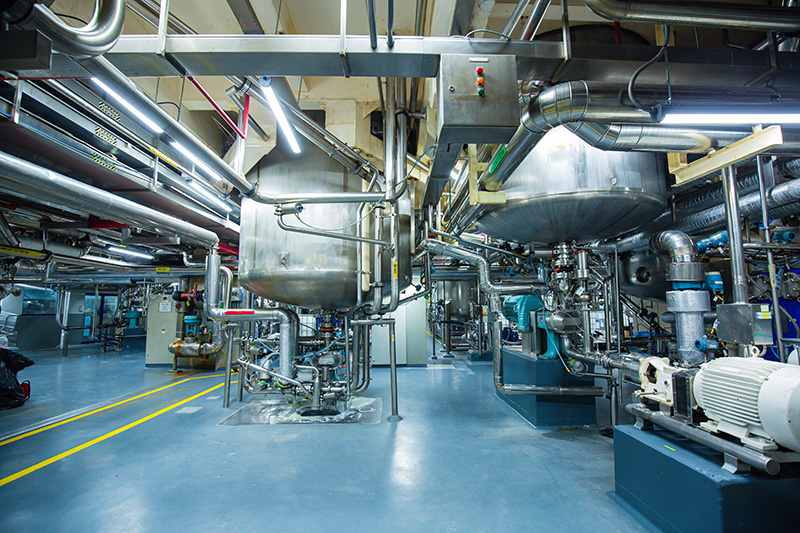

The malt grains, from which the fermentable sugars are extracted, thanks to cavitation, can be reduced to less than 100 microns in size in a few minutes, completely skipping the grinding.

These very small dimensions increase not only the speed with which the starch will pass to the must (the sweetened water that is boiled with the hops before being cooled and transformed into beer by the yeast) but, above all, they optimize the process to the point that everything passes starch making final washing with malt water unnecessary to try to extract the last traces of precious starch.

It should also not be underestimated that the greater speed and efficiency also allow that the transformation into simpler and fermentable sugars can take place at lower temperatures, and therefore the unpleasant and volatile gases degass more quickly, denaturing the enzymes in the must and allowing to mix easily the flavors of hops.

Therefore, it is clear that the must have to boil for a fraction of the time previously necessary, drastically reducing production times and costs.

A further “undesired” effect that emerged during the experiment was a drastic reduction in the gluten in the must and beer produced with 100% barley malt.

The experimental tests indicate the degradation of the proline residues, the amino acid responsible for the problems of intolerance and sensitivity to gluten, due to the improvement of the assimilation of the proline by the yeasts.

Considering that the current systems used to eliminate gluten mostly alter the taste and quality of beer, this “undesired” effect opens up numerous and interesting scenarios.